Starbucks Hits the Bong Designer In the Wallet

December 5, 2016 |The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California recently granted Starbucks’ motion for a default judgment against James Landgraf, an individual responsible for the design and sale of glass bongs, clothing, and other novelties that infringed certain logos owned by Starbucks. Starbucks Corp. v. Glass, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 145694 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 20, 2016). The court awarded Starbucks a default judgment in the amount of $410,580 in damages and attorneys’ fees against Mr. Landgraf.

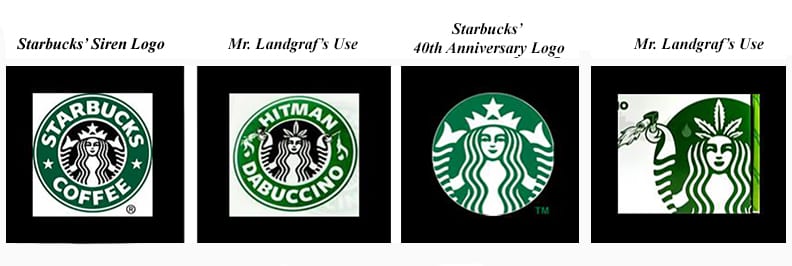

The java giant claimed that Mr. Landgraf designed, and sold to co-defendant Hitman Glass, certain products in his “Dabuccino” line that infringed intellectual property rights affiliated with Starbucks’ Siren Logo and the 40th Anniversary Siren Logo (“Starbucks Marks”). The Starbucks Marks, and those used by Mr. Landgraf, are shown below:

Starbucks alleged the following causes of action in its complaint: trademark dilution, copyright infringement, trademark infringement, and false designation of origin. Unlike Hitman Glass, Mr. Landgraf did not respond to Starbucks’ complaint prompting Starbucks to seek entry of a default judgment.

Trademark Dilution

The court found that Starbucks pled meritorious claims against Mr. Landgraf for both federal trademark dilution under the Lanham Act and state trademark dilution under the California Business and Professions Code. Under both federal and state law, in order to assert a dilution claim, a plaintiff must demonstrate that the: (1) mark is famous and distinctive; (2) defendant is using the mark in commerce; (3) defendant’s use began after the mark became famous; and (4) defendant’s use of the mark is likely to cause dilution by blurring or dilution by tarnishment.

The court concluded that Starbucks satisfied the above criteria. First, the Starbucks Marks are unmistakably famous. In order to determine whether a mark is famous, a court examines: (i) the duration, extent and geographic reach of advertising and publicity relating to the mark; (ii) the volume, amount and geographic extent of sales of goods or services offered under the mark; (iii) the extent of the mark’s recognition; and (iv) whether the mark was registered. Here, the Starbucks Marks are well-known due to their use in 22,000 retail locations worldwide. Further, these registered marks have been in use, respectively, for over twenty years and over five years. Lastly, the Starbucks Marks are involved in billions of transactions every year.

The court also found that it is clear that Mr. Landgraf has been using the Starbucks Marks to sell his products because substantially similar marks have been used on his glass bongs, hat pins, stickers, and t-shirts. The court determined that the sale of the “Dabuccino” products began in 2015, long after the Starbucks Marks became famous and that the “Dabuccino” products were expressly inspired by the fame and relatability of the Starbucks Marks.

Finally, the court found that the use of the Starbucks Marks is likely to cause dilution by blurring. Dilution by blurring is established when the association arising from the similarity between a mark and a famous mark impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark. The following factors are considered in a dilution by blurring analysis: (1) the degree of similarity between the mark and the famous mark; (2) the degree of inherent or acquired distinctiveness of the famous mark; (3) the extent to which the owner of the famous mark is engaging in exclusive use of the mark; (4) the degree of recognition of the famous mark; (5) whether the use of the mark intended to create an association with the famous mark; and (6) any actual association between the mark and the famous mark.

The court concluded that it was plain that the first five factors show that Mr. Landgraf’s infringing use is likely to cause dilution. Starbucks demonstrated that the logos are substantially similar, the Starbucks Marks are distinctive and arbitrary as they are used to sell coffee, and its marks are highly recognizable. Moreover, Starbucks has sought to enforce its marks through registration and monitoring of distribution channels, and public statements by the defendants in this action indicate that the defendants intended to create an association with the Starbucks Marks. As a result, the court found the dilution claims meritorious.

Copyright Infringement

The court determined that Starbucks also pled a meritorious copyright infringement claim against Mr. Landgraf. In order to plead a claim for copyright infringement, Starbucks was required to show: (1) ownership of a valid copyright; and (2) copying of constituent elements of the work that are original. The second element is satisfied by showing that the infringer had access to the work and the two works are “substantially similar.”

Starbucks satisfied the first element by attaching valid copyright registration certificates to its complaint. The second element was satisfied based on a side-by-side analysis of the works, which clearly indicate that Mr. Landgraf’s designs are substantially similar to Starbuck’s copyrighted designs.

Trademark Infringement and False Designation of Origin

The court concluded that Starbucks pled meritorious claims for trademark infringement and false designation of origin. The court began its analysis by outlining the relevant factors that are balanced in assessing a likelihood of consumer confusion – – the linchpin to a claim for trademark infringement. Those factors include: (1) the strength of the mark; (2) proximity of the goods; (3) similarity of the marks; (4) evidence of actual confusion; (5) marketing channels used; (6) type of goods and the degree of care likely to be exercised by the purchaser; (7) defendant’s intent in selecting the mark; and (8) likelihood of expansion of the product lines.

The court found that virtually all of these factors favored Starbucks. After concluding that the Starbucks Marks were famous, the court determined that certain of the goods sold by Mr. Landgraf, that is, t-shirts and pins, overlapped with goods protected by Starbucks’ trademark registrations. And based on the above images, the court also concluded that the logos used in connection with the “Dabuccino” product line were virtually identical to the Starbucks Marks.

With respect to evidence of actual consumer confusion, the court pointed to certain comments on social media to support its finding that consumers have already associated Mr. Landgraf’s products with Starbucks. Likewise, the court concluded that the products sold by Starbucks and Mr. Landgraf traveled within the same marketing channels as both product lines were available for sale online. In addition, because the products at issue were less-expensive novelty products, the court determined that such products would not be carefully scrutinized by consumers.

Finally, the court concluded that Mr. Landgraf’s conduct demonstrated a clear intent to infringe the Starbucks Marks. To support this finding, the court highlighted the fact that Mr. Landgraf’s products included certificates of authenticity featuring the infringing logos.

Remedies

As a result of the conduct outlined in the complaint, Starbucks requested: (1) the issuance of a permanent injunction; (2) statutory damages under the Copyright Act; (3) compensatory damages under the Lanham Act; and (4) attorneys’ fees.

The court, however, did not grant a permanent injunction because Starbucks did not demonstrate that it suffered irreparable injury. To this point, Starbucks argued that it faced a threat of loss of prospective customers, goodwill, and reputation as a result of Mr. Landgraf’s infringement. The court disagreed and reasoned that Starbucks did not show how any of these particular harms had actually transpired as a result of Mr. Landgraf’s conduct. The court also found Starbucks’ position that there were no adequate remedies available at law unequally unpersuasive.

The court did, however, award Starbucks monetary damages. Specifically, the court awarded Starbucks $300,000 in statutory damages under the Copyright Act. The Copyright Act grants the court broad discretion to award up to $150,000 in statutory damages per infringed work. Here, based on Mr. Landgraf’s willful infringement of Starbuck’s two copyrighted works, together with Starbuck’s inability to identify its exact damages, the court concluded that the $300,000 award was reasonable. In addition, under the Lanham Act which authorizes, among other relief, the disgorgement of a defendant’s profits, the court awarded Starbucks an additional $99,000 representing the amount of money that Mr. Landgraf received from Hitman Glass for his work on the “Dabuccino” product line.

Finally, the court granted Starbucks’ request for attorneys’ fees. However, in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, the local rules contain restrictions on awards of attorneys’ fees within the context of default judgments. Specifically, where the default judgment is more than $100,000, and there is an applicable statute – – like the Copyright Act or Lanham Act – – that provides for the recovery of attorneys’ fees, the court must set attorneys’ fees at the fixed sum of $5,600 plus 2% of any amount over $100,000 that is awarded in the judgment. As applied here, the court awarded Starbucks a total of $11,580 in attorneys’ fees.